Tango developed in an environment similar to American jazz. A collision of cultures and musical and dance idioms created a new music and dance form. At the time of tango's origin and during its golden age, Argentina was full of people, primarily men, who had emigrated from the homelands of their youth, primarily Europe, to the rough and tumble environment of Argentina. Their sense of alienation, and longings for homeland, sweethearts, and meaningful lives can be found in the poetic lyrics to numerous tangos such as "Naranjo en Flor" and "Charlemos," that are rich in multiple interpretation.

Naranjo en Flor - Orange Tree in Bloom (1944)

Music by Virgilio ExpositoLyrics by Homero Exposito (1918-1987)

English Translation by Sergio Suppa

| Era mas blanda que el agua,

que el agua blanda, era mas fresca que el rio, naranjo en flor... Y en esa calle de estio,

Primero hay que saber sufrir,

Despues, que importa el despues?

Que le habran hecho mis manos?

Dolor de vieja arboleda,

|

She was softer than water,

than soft water, she was fresher than the river, flowering orange tree... In that summer street,

First one has to know suffering,

Afterwards, does it count?

What did my hands do to her?

Pain of an old grove,

|

The beauty of these lyrics show the great Homero Exposito's creativity

and poetry, but they also tell of lost love, a love that existed in another

time and place—a love that strikes with intensity, in a transient way,

like the perfume of flowering orange trees in spring, or like the sense

of connection during a tango. From the lyrics, one gets a sense of

separation, suffering, a longing for the past, possibly remorse or a questioning

of what might have gone wrong, as the tango comes to a close. The

lost love may be a woman, youth, spirit, a homeland symbolized by orange

groves that were left behind (possibly in Spain), or simply the intense

feeling of connection that existed for the three minutes of a tango dance.

Charlemos - Let's Chat (1941)

Music and Lyrics by Luis RubinsteinTranslation by Sergio Suppa, Frank Sasson and Alberto Paz

| Belgrano sesenta once?

Quisiera hablar con Renee... No vive alli?... No, no corte... Podria hablar con Ud.? No cuelgue... la tarde es triste.

Charlando soy feliz...

Hablemos de un amor...

Charlemos, nada mas.

Charlemos, nada mas,

Que dice? Tratar de vernos?

No puedo.. no puedo verla.

|

Belgrano 6-0-1-1?

I would like to talk to Renee... She doesn't live there?... No, don't hang up... Could I talk with you? Don't hang up... the afternoon is gloomy.

Chatting makes me happy...

Let's talk about an affair...

Let's talk, nothing else.

Let's talk, nothing else,

What are you saying? To try to see each other?

I can't... I can't see you...

|

At one level, "Charlemos" might be interpreted as being about a lonely man whose blindness isolates him from the rest of society. He attempts to fulfill his need for love by talking to a stranger on the telephone; knowing that he will never be able to see or meet her because he is unwilling to impose his handicap on a healthy woman.

The last lines need not be interpreted so literallly, however. The speaker might be figuratively blinded by the sorrow of losing Renee's love and seeking solace from another woman. His statement Renee yo se que no existe... I know Renee does not exist... would be also interpreted figuratively as meaning that Renee no longer exists for him.

When the speakers says,

| Hablemos de un amor...

Seremos ella y el Y con su voz Mi angustia cruel sera mas leve. |

Let's talk about an affair...

We'll be her and him and with your voice My cruel anguish will be milder. |

he would be suggesting that he and the stranger pretend that they are Renee and her new lover. Their pretense will soften the anguish and sadness he feels from being a spurned lover on this gray afternoon. The stranger's feminine voice brings him solace, but in the end he realizes that will not change the fact that she is not Renee, and he is not Renee's new lover. When she suggests meeting, he refuses because he prefers illusion.

Perhaps Renee represents the speaker's homeland, and the stranger on the line represents Argentina. Perhaps because it could not support him, the man left his homeland for Argentina. Now he feels rejected and betrayed by his homeland—which he cannot find, to which he cannot return, and whose existence he now doubts. In his anguish and blindness, he has sought to fill the feelings for his homeland with Argentina, but cannot do so. When he is confronted with the reality of his existence (when the stranger suggests they meet), he prefers illusion.

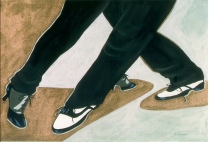

Dancing Argentine tango itself can create such feelings—particularly when it is danced with the proper stranger. For the length of a well-danced and magically sublime tango, we touch each others' hearts in ways words cannot match. We get a sense of returning to a home where we belong, where we loved and felt loved—even if that home exists only in the depths of our souls rather than our personal history. Then the song ends, the dance is over, and we return as strangers to our respective tables or sides of the room. Worse, we can begin talking and find that all we have in common is a history of well-danced tango together. Maybe it is better for us to remain strangers with our illusions, as the speaker decides in "Charlemos."

In Paper Tangos, Julie Taylor quotes a young milonguero as saying, "In a tango, together with the girl—and it does not matter who she is—a man remembers the bitter moments in his life, and he, she, and all who are dancing contemplate a universal emotion. I do not like the woman to talk to me when I dance tango. And if she speaks, I do not answer. Only when she says to me 'Omar, I am speaking,' I answer, 'and I, I am dancing.'"